Saturday, 29 September 2018

Saturday, 22 September 2018

How old is the Bible?

|

|

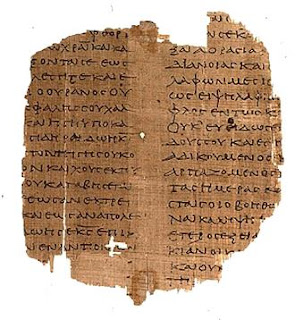

Fragment of the Bible written in Greek on papyrus and dating from about 400 bc

|

The Bible is a library and not a book. It was written over a very long period of time, so some bits are older than others.

Oldest/earliest

- Old Testament The oldest part of the Old Testament is probably the so-called ‘Song of Miriam’ in Exodus 15:1–21. It records a song sung by Moses’ sister to celebrate the destruction of the Egyptian army. Miriam probably wrote it in about 1400 bc.

- New Testament St Paul’s first letter to a Church in Thessalonika is the earliest part of the New Testament. Some scholars think it was written in 50 ad, only 15 years after the crucifixion, though internal evidence suggests he wrote it in 60 or 61 ad.

Latest/most recent

- Old Testament The most recent part of the Old Testament to be written are chapters 7–12 of Daniel, which were written in about 140 bc. Their subject matter claims to come from much earlier.

- New Testament Probably the most recent part of the Bible is 2 Peter, which may have been written as late as 120 ad. It is usually dated to 80–90 ad. (St Peter was killed in 68 ad, making it the latest date he could have written it himself.)

For more information, go to:

https://www.biblica.com/resources/bible-faqs/when-was-the-bible-written

https://www.allabouttruth.org/when-was-the-bible-written-faq.htm

https://www.allabouttruth.org/when-was-the-bible-written-faq.htm

The Prophet Amos

Amos was the first of the so-called ‘writing prophets.’ The book bearing his name relates to the time around 760 bc.

The story starts in a small but significant market town, Bethel — then, the capital of Israel and location of an important altar. The book starts with a shrill denunciation: ‘Thus says the Lord: for three transgressions of Damascus, and for four, I will not turn away the punishment.’ The people would have heard this message with glee, delighted that God was angry with their old enemy. Few of them noticed the full implications of the prophecy they cheered so heartily: if God was announcing His punishment on Damascus, then He must be a God whose power extended not only over Israel but over other nations as well. The old idea of God as Israel’s own, exclusive, national God could no longer survive after Amos began to teach that God was supreme over all nations.

Amos then announced God’s anger against other traditional enemies such as Ammon and Moab — the location of the towns describing a spiral that gets ever closer to home. A roar of protest would have greeted Amos’ final statement: ‘For three transgressions of Israel, and for four, I will not turn away my punishment’ (Amos 2:6). It was unthinkable that a territorial God would punish His own people: what had they done to make Him angry? Surely they had not failed to offer sacrifices?

Into the shocked hush, Amos explained the Lord’s denunciations saying, for example: 'Because you have sold the righteous for silver, and the poor for a pair of shoes’ (Amos 2:6). Amos continued: ‘[God says] I hate, I despise your feast days … though you offer me burnt offerings and meat offerings, I will not accept them’ (Amos 5:21). Who ever heard of a God not accepting the elaborate rituals of religion? The idea was surely preposterous. From the crowd, some one must have shouted, ‘Tell us, then, what does Yahweh want?’ Amos answered with words he received from God: ‘Let judgement run down like waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream’ (Amos 5:24).

Amos was saying that God wanted right actions; wrong actions followed by a quick visit to the altar shrine could not placate God. To Amos, such action was trying to bribe God, effectively asking Him to turn a blind eye to the despicable treatment of their fellow Israelites. Rather, Amos saw God as being righteous and holy. This idea may be commonplace today, but it was a strange new doctrine to these people, and they struggled to understand it.

This message was so new, so subversive of the old ways of doing religion, that Amaziah the High Priest feared for the maintenance of his shrine. To him, Amos’ ideas were theologically unsound — sacrilegious even. After Amos den ounced the sanctuaries themselves (Amos 7:9), the high priest sent an urgent message to the King, Jeroboam, and had Amos thrown out.

Amos went to the mountaintop village of Tekoa, a day’s walk away to the south, where he dictated to one of his followers the prophecies he had spoken to Israel. The scribe somehow managed to capture the rhythm and form, and the tremendous power of the prophecies, which abound in judgements on national and international affairs.

Scholars believe the book of Amos was the first book in the Old Testament to be completed. The material in other books may be older, but has been edited, often heavily. Amos ushered in the prophetic movement of the eight century bc, which established a high-water mark in the spiritual history of Israel.

For more information, go to:

https://thebibleproject.com/explore/Amos

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amos_(prophet)

Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hammarskjöld was born in 1905. He was the youngest son of the Swedish Prime Minister; his mother was a woman of great spirituality. Both parents came from old, noble families, so he spent most of his childhood within the ancient walls of Uppsala Castle.

Dag attended Uppsala University (Sweden’s finest). He was a brilliant scholar so the University proclaimed him its outstanding student of his year. He read the humanities, with emphases on linguistics, literature, and history.

His main intellectual and professional interest for some years, however, was political economy. He took a second degree at Uppsala in economics in 1928, a law degree in 1930, and a doctorate in economics in 1934.

In all, Dag served Swedish national affairs and international relations for 31 years in roles that included being secretary of a governmental committee on unemployment, under-secretary in the Swedish Ministry of Finance, and head of the Bank of Sweden.

Dag played a pivotal role in giving Sweden a key voice in reshaping the world order after World War II. His steady diplomacy during the Cold War helped shape global politics; he personally prevented many armed conflicts.

Dag became the third Secretary General of the United Nations (1953–61), and the first to be elected unanimously. He enhanced the effectiveness and prestige of the UN. To many, he was the UN’s best ever leader and his appointment was said to be the most notable success for the UN at that time. John F. Kennedy described him as ‘the greatest statesman of our century.’

He died in controversial circumstances in September 1961 when his plane crashed on a peace mission in Africa. The same year he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, posthumously, which is vanishingly rare.

His extraordinary moral integrity was a direct result of his deep Christian faith. In a brief piece written for a radio program in 1953, he spoke of the influence on his life: ‘From generations of soldiers and government officials on my father’s side I inherited a belief that no life was more satisfactory than one of selfless service to your country – or humanity. This service required a sacrifice of all personal interests, but likewise the courage to stand up unflinchingly for your convictions. From scholars and clergymen on my mother’s side, I

inherited a belief that, in the very radical sense of the Gospels, all men were equals as children of God, and should be met and treated by us as our masters in God.’

inherited a belief that, in the very radical sense of the Gospels, all men were equals as children of God, and should be met and treated by us as our masters in God.’

He never married, so chose to redirect his astonishing gifts to the service of God and humanity. ‘I am the vessel. The draft is God’s. And God is the thirsty one.’ He often compared his life of service to that of a religious vocation. Indeed, his life was almost monastic in the way he dedicated everything he did to God. And he corresponded widely with Christian activists, writers and people like Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton.

After his death, in 1963 his estate published his ‘journal’, which they entitled Markings. It reveals the inner man. He himself described it as ‘A book concerning my negotiations with myself – and with God.’ Most of its entries are spiritual truths given artistic form. The book contains a great many references to death, such as ‘Do not seek death. Death will find you. But seek the road which makes death a fulfilment’.

Although dated in parts, the book soon had an enormous following.

For more information, please read:

Pray as you can (not as you can't)

Apparently, the people living within the Arctic Circle use many dozens of words to describe snow … because it’s such a major part of their lives.

By contrast, we use a mere handful of words. In the same way, most of us use the single word ‘prayer’ to describe all our interactions with God; but people who make prayer their way of life (such as monks and nuns) use a wide variety of terms to describe different types of prayer.

Apparently, the people living within the Arctic Circle use many dozens of words to describe snow … because it’s such a major part of their lives.

By contrast, we use a mere handful of words. In the same way, most of us use the single word ‘prayer’ to describe all our interactions with God; but people who make prayer their way of life (such as monks and nuns) use a wide variety of terms to describe different types of prayer.

At its most basic level, prayer is simply speaking with God. Like any other conversation, it has two aspects, speaking and listening. Many Christians spend more time speaking and less time listening, particularly when they are young Christians. As they grow in maturity, they realise the importance of learning how to listen to God.

How do I talk to God?

Praying might sound difficult, but it isn’t. At heart, prayer is talking with God. It is perfectly OK to talk aloud to God, but (except in church services) most people talk to Him silently. You could call it ‘talking in your head’; the Bible sometimes calls it ‘the thoughts of our hearts.’

Should I pray?

Definitely, yes! Prayer is an encounter with God. Just as we get hot when we stand in front of a hot fire, so we acquire something of God’s holiness when we pray.

Jesus prayed often. He sometimes prayed all night (Mark 1:35–37). Prayer was obviously so important to him that his disciples implored him to teach them how to pray, as another holy man, John the Baptist, had been teaching his own disciples. We give the name Lord’s Prayer to the words Jesus taught his disciples in response, though some Christians call it ‘the Our Father’ or ‘the Pater noster’ (which comes from the Latin for ‘our Father’).

The Bible gives us two versions of the prayer: Luke 11:2–4 and Matthew 6:9–13. We recite the longer version from Matthew during each service. The version from Luke is shorter, and contains much less detail: ‘Father, hallowed be your name, your kingdom come. Give us each day our daily bread. Forgive us our sins, for we also forgive everyone who sins against us. And lead us not into temptation.’

Why do people talk about a ‘prayer life’?

We get to know people as our relationship with them develops. That process of ‘getting to know’ involves learning about the other person: what they like, dislike, and so on. It may even explain why we want the relationship. In the same way, God wants all Christians to enter a relationship with Him and get to know Him.

This ‘getting to know God’ involves more than knowing about Him. Like all relationships, it requires a level of commitment. In other words, learning what it feels like to be in God’s presence, coming into His presence more and more often, and for increasing lengths of time.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)